22 October 2020

Isaac Horton (1821 – 1880)

By Professor Carl Chinn

Professor Carl Chinn shares the extraordinary story of the man behind The Grand Hotel Birmingham.

Isaac Horton was born in 1821 to Harriet and Benjamin, a butcher in West Bromwich – a town on the cusp of rapid growth driven by the power of industry. An aspiring man, Benjamin Horton did well and in a period when the vote was restricted to a few men, he was enfranchised by owning the freehold of his butcher’s shop in Lyng Lane. He continued to work there until the later 1850s, by which time his income was derived from his ownership of other properties and when he died in 1881, he classified himself not as a tradesman but as a ‘gentleman’. Benjamin Horton left £2745, a substantial sum bearing in mind that an unskilled labourer would not earn even £1 a week. Still, this legacy was tiny compared to that of his oldest son, Isaac. He died a few months before his father and left a personal estate of £200,000, to which could be added property worth half a million pounds in Birmingham, West Bromwich, Wolverhampton and Walsall and which would become part of the Horton Estate.

The tribute on Isaac Horton’s memorial at his grave in Key Hill Cemetery is from Shakespeare’s Hamlet: ‘He was a man, take him, for all in all I shall not see his like again’. They are most meaningful words for Isaac Horton’s achievements can only be regarded as astounding. Though his family was of the middling ranks, they were not wealthy when he began his business life and it was through his own endeavours that he became one of the most important figures in Victorian Birmingham. Aged 20 in 1841, he was working at his father’s butcher’s shop in West Bromwich but filled with ambition as he must have been, he soon set off on his own account. A decade later, he was a butcher and provision merchant on the town’s High Street, its main shopping thoroughfare, and employed eight servants and assistants. Five of them, including a housekeeper, lived with him on the premises.

Horton’s at 8 Spiceal Street is on the left, overlooking the traders in the Bull Ring’s outdoor market in the late nineteenth century. (BirminghamLives Archive).

A leading figure amongst local tradesmen, in 1852 and in the parish church of Aston, Isaac Horton married Sarah Scolefield, whose father was also a butcher. Later that year, Isaac sold his business in West Bromwich to focus on a new venture trading as a wholesale pork butcher in Wolverhampton. He was highly successful and within just three years, it was reported that he had ten pork shops in the Black Country, including one in Dudley and three in Wolverhampton at Bilston Street, Dudley Street and High Green (later Queen’s Square). It seems that he and his wife and their three oldest sons lived at High Green, which boasted a spacious retail shop and dwelling house, comprising four chambers, closet, three sitting rooms and kitchen, along with offices and yard. As for the Dudley Street premises, Isaac Horton operated from there as a provision merchant and cheese factor as well as bacon curer; whilst at Bilston Street, he had extensive machinery fitted up so that ‘day after day, week by week, pigs were driven in, slaughtered, and cured to supply his numerous places of business in the Black Country’. He also sold large quantities of bacon to Wales and elsewhere. So extensive was his business that it was said that he slaughtered between 600 and 800 pigs a week, and many more in the lead up to Christmas.

He was a man, take him, for all in all I shall not see his like again

Another photograph taken in the late nineteenth century showing Horton’s ham and bacon warehouse on the left. (BirminghamLives Archive).

Always looking for new opportunities, in 1858 Isaac opened up as a wholesale and retail pork butcher at 8 Spiceal Street, one of the most prominent positions in Birmingham’s Bull Ring, the focal point of the town’s traders. A large building, it was also home to the Horton family, a pork butcher’s assistant and two housemaids. From this ham and bacon warehouse in Spiceal Street, Isaac Horton bought and slaughtered pigs to supply customers and his own shops with home cured bacon and English provisions as well as those from America imported via Liverpool. He quickly made a strong impression in Birmingham. In descriptions of the Christmas Meat Show of local butchers in December 1858, he was noted as having an immense stock of prime pork. At the recent Cattle Show at Bingley Hall, he had even purchased six first-class pigs from the sty of Prince Albert, another 40 large and prime hogs, and well over 100 first-rate pigs from the best regional styes.

Isaac Horton kept a close control of his business and at the end of each week, he would travel from Birmingham by train to collect the takings from his pork shops in the Black Country. Knowing exactly what time he would arrive at their nearest station, his managers waited for him on the relevant platform to hand over the money in a canvass bag. Once he arrived in Wolverhampton, the receipts would be checked and signed off. Along with this extensive business, he became a large-scale provision merchant and cattle dealer and soon he would be noted for his extensive property portfolio.

As a young man in the 1840s, Isaac Horton had bought houses in West Bromwich. Praised as one of the shrewdest and thriftiest of men who invested his savings, he went on to purchase the freeholds of his pork shops. By 1862, when he was still only 41, he owned the freehold of a number of premises in the busiest parts of central Wolverhampton as well as shops with houses in Dudley, West Bromwich and Walsall. In addition, he had bought his two pork shops in Dale End and Smallbrook Street, Birmingham. He would go on to buy at cheap prices properties elsewhere in the city on long leases on. Then, in the 1870s, he made a major leap of imagination and capital investment by moving into New Street, which was vying with Colmore Row to become Birmingham’s most prestigious thoroughfare. Isaac Horton made a major contribution to that development by having his builders demolish older buildings and replace them with grand structures such as the Midland Hotel (later the Burlington Hotel). Close to the original entrance of New Street Station, it was admired as elegant and spacious after its opening in January 1874.

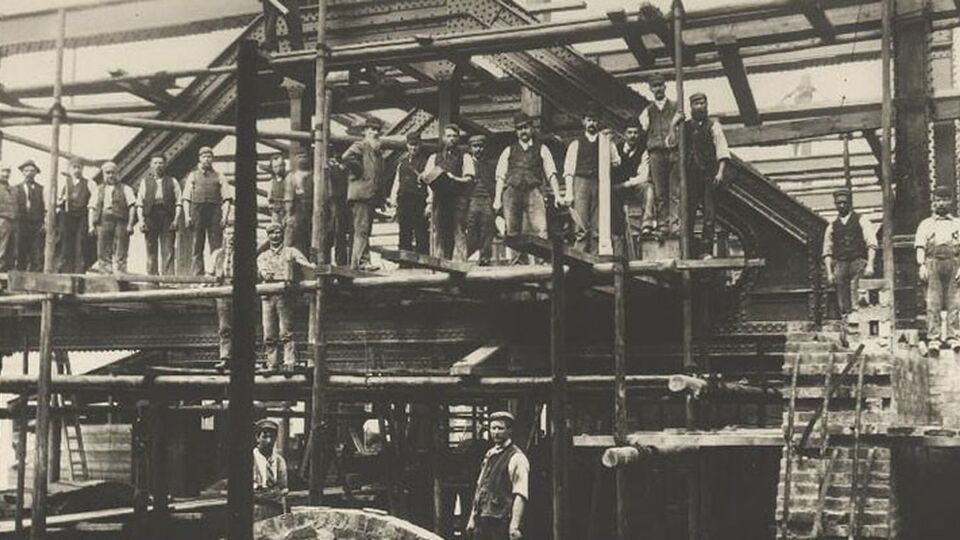

Workers on one of Isaac Horton’s new buildings. (Horton Estates).

Soon afterwards, Isaac Horton joined the middle-class move to Edgbaston by renting Ferndale at 222 Hagley Road, advertised as a first-class family residence with spacious garden and grounds in the best-part of the district. Less than two years before his untimely death, the most striking and important of Isaac Horton’s buildings was opened: the Grand Hotel on Colmore Row. Along with New Street, Colmore Row was in the throes of an architectural transformation making it, as one commentator pronounced, ‘one of the stateliest avenues in the kingdom’. This radical change began in the early 1870s with actions taken by the Council. It instigated work on the palatial-style Council House at the Victoria Square end of Colmore Row and carried out wide-ranging improvements along the whole street by removing projecting buildings and road widening. With an astute eye for opportunities for high-quality developments, Isaac Horton was amongst the first to recognise the emergence of Colmore Row as one of the most important streets in Birmingham, a process he himself stimulated with the building of the Grand Hotel on land bought between Church Street and Livery Street. Previously occupied by several large houses, this spot was very close to the Snow Hill Station of the Great Western Railway and he was acutely aware of the trade a hotel could gain from railway passengers.

Now an extremely wealthy man, Isaac Horton was focusing increasingly on his building projects and in September 1880, he offered for sale the goodwill and possession of his very extensive and highly profitable pork butcher’s business in Spiceal Street. With its pig yard, slaughter and hanging houses, sausage room, bakery, salting cellars, drying room and other facilities it was regarded as one of the most compact and complete pork butchering establishments in the kingdom. Unhappily, within weeks, he was dead. Always intent on closely supervising his investments, he been overseeing building work in High Street, Birmingham when he was taken ill, dying aged 59 in November 1880.

According to newspaper reports, ten years previously Isaac Horton had slipped from a ladder, sustaining an internal injury which rendered him liable to seizures, one of which was fatal. The obituaries in local newspapers emphasised that whilst he had taken no part in municipal or political affairs, he was esteemed. By personal industry and successful speculation, he had amassed a large fortune and an estate including nearly one-third of the property in New Street.

About Professor Carl Chinn

Professor Carl Chinn MBE Ph.D. F.Birm.Soc. is a social historian with a national profile, writer, public speaker, and teacher. He is the author of 34 books and most recently, Peaky Blinders: The Real Story (John Blake 2019) was a Sunday Times bestseller. His writings are deeply affected by his family’s working-class Birmingham background and he believes passionately that history must be democratised because each and every person has made their mark upon history and has a story to tell.

Share this article